How the South was Lost

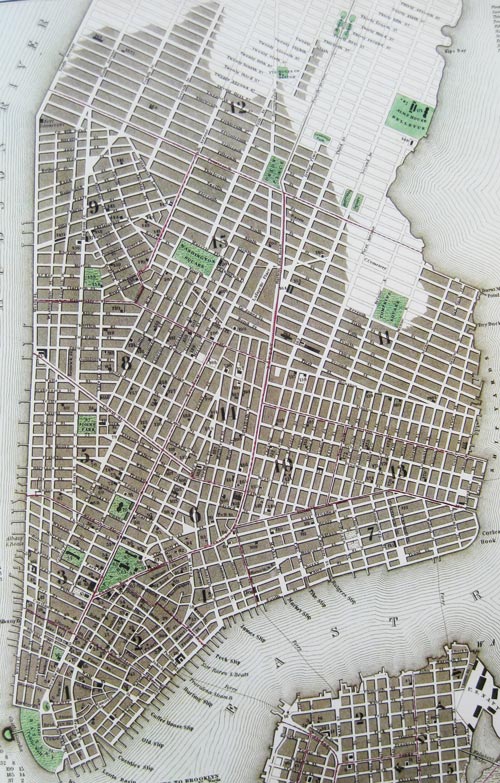

Vivek Nemana is an economics graduate student in New York University and a student worker at DRI. UPDATE: Art Carden makes an important emphasis regarding this post and contibutes an ungated link to his paper. See comments/bottom of post.

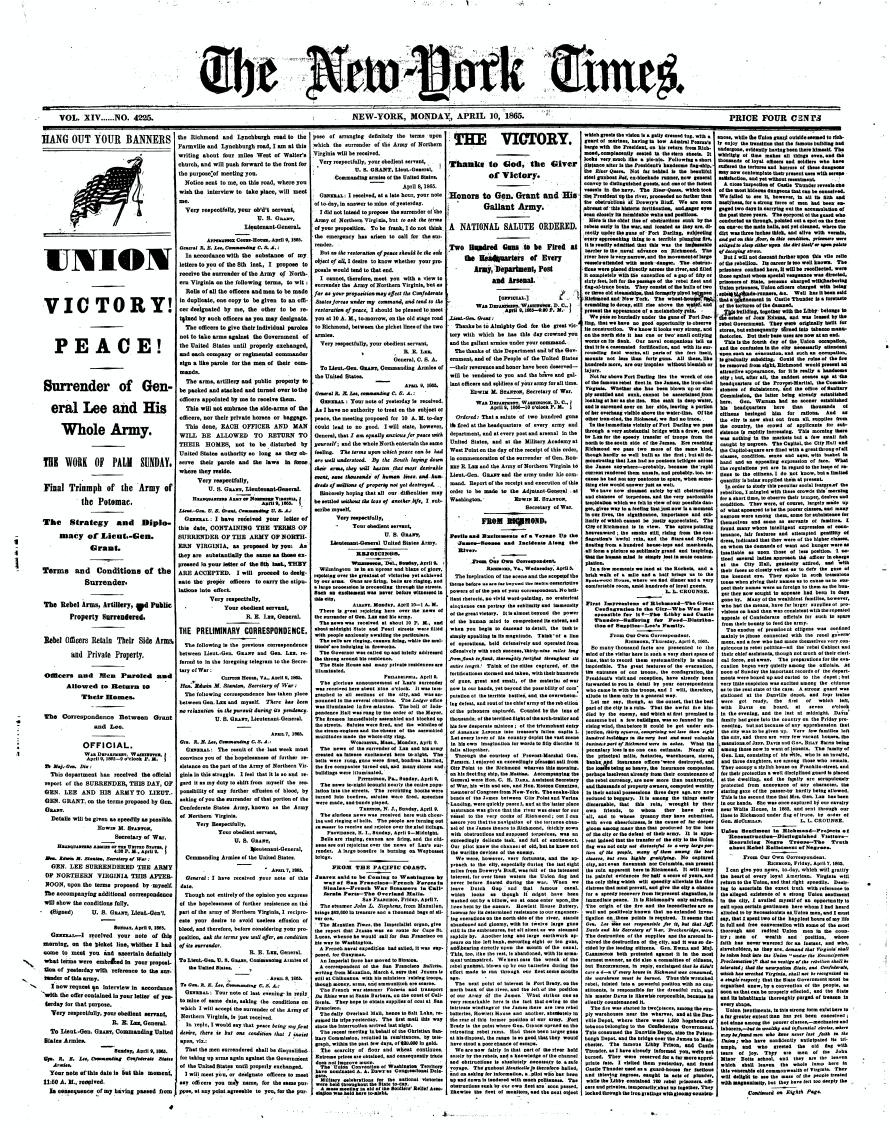

Last week marked 150 years since the beginning of the Civil War. Victory for the North meant more than the preservation of the Union. It meant that slavery could no longer continue as a viable factor of economic productivity. It meant the end of the terrible institution that deemed human beings were property, and heralded an important step in the long American struggle for universal human rights.

But it also reinforced the cleavage between an industrial, prosperous North, and a rural, underdeveloped South, a distinction that persists in some ways even today.’ The Union won in large part because of its industrial advantage, and its victory installed in the South what should have been better conditions for economic growth – liberal, more universal property rights and the abolition of slavery.

So what happened? A 2009 paper by Art Carden{{1}} argues that it was the very insertion of these new freedoms and property rights into a society designed for slavery that led to the divergent development of North and South.

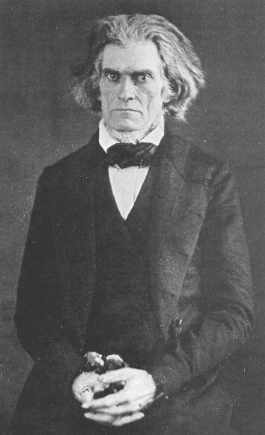

Before the War, Southern social networks were based on hegemonic bonds relying on power imbalances and the threat of violence. The South was heavily invested in racial subjugation – slavery directly accounted for over a quarter of the GDP. The region spent an enormous amount of resources to justify slavery, hiring silver-tongued apologists like John C. Calhoun to spin slavery as humane. In this light, slavery was an economic institution that was designed for racially hegemonic society.

While the Civil War radically restructured Southern laws to promote racial equality and property rights, the hegemonic bonds were resistant to change. This generated a major friction, Carden writes, that manifested through the racist Jim Crow laws and, most gruesomely, lynchings that openly defied the new freedoms for blacks.

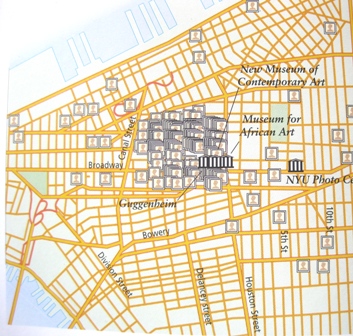

The backlash against black self-determination, the politically-enforced segregation, and the conviction that one race was inferior were societal phenomena that hurt economic growth. For example, segregation and racist violence meant that markets were smaller and the division of labor shallower than it could have been. Mutual fear and distrust made contracting and doing business across racial boundaries more expensive. As a result, Carden writes, “Southern entrepreneurs, innovators, and laborers relied more heavily on kinship networks and informal arrangements than on formal markets.”

And these factors were self-reinforcing, Carden argues, breeding a cycle of mistrust, ignorance and poverty.

Gary Becker once wrote that people lose out on the potential gains from trade if one group is able to indulge in “tastes for discrimination” against another. As the legacy of slavery wound its way into postbellum Southern society and politics, it hindered the way freedom and property rights should have boosted the economy, denying the South the full bounty of American development.

[[1]]Here's the ungated version.[[1]]

---------

Photo credit: New York Times and Wikispaces

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality