1) “State failure” is leading to confused policy making.

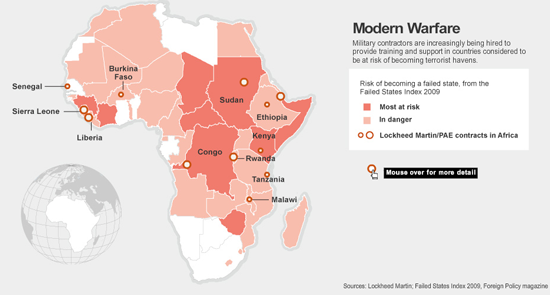

For example, it is causing the military to attempt overly ambitious nation-building and development to approach counter-terrorism, under the unproven assumption that “failed states” produce terrorism.

2) “State failure” has failed to produce any useful academic research in economics.

You would expect a major concept to be the subject of research by economists (as well as by other fields, but I am using economics research as an indicator). While there has been research on state failure, it failed to generate any quality academic publications in economics. A search of the top economics journals1 reveals that “state failure” (and all related variants like “failed states”) has been mentioned only once EVER. And this article mentions the concept only in passing.2

3) “State failure” has no coherent definition.

Different sources have included the following:

a) “Civil war”

b) “infant mortality”

c) “declining levels of GDP per capita”

d) “inflation” 3

e) “unable to provide basic services”

f) “state policies and institutions are weak”

g) “corruption”

h) “lack accountability” 4

i) “unwilling to adequately assure the provision of security and basic services to significant portions of their populations” 5 (wouldn’t this include the US?)

j) “inability to collect taxes”

k) “group-based inequality… and environmental decay.” 6

l) “wars and other disasters”

m) “citizens vulnerable to a whole range of shocks” 7

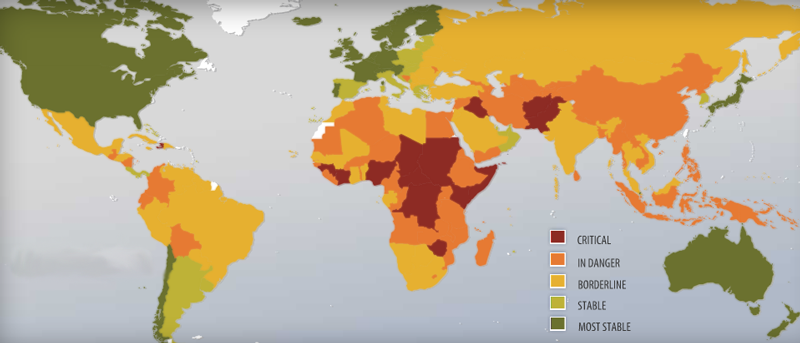

Most of these concepts are clear enough in themselves, and often apply to a large number of countries. But is there any good reason to combine them with arbitrary weights to get some completely unclear concept for a smaller number of countries? “State failure” is like a destructive idea machine that turns individually clear concepts into an aggregate unclear concept.

4) The only possible meaningful definition adds nothing new to our understanding of state behavior, and is not really measurable.

A more narrow definition of “state failure” is: a loss of the monopoly of force, or the inability to control national territory. Unfortunately this is impossible to measure: how do you know when a state has control? The only data I have been able to find that might help comes from the Polity research project that classifies the history of states as democracies or autocracies. 8 It describes “interregnums” that sound like the narrow “state failure” idea:

A "-77" code for the Polity component variables indicates periods of periods of “interregnum,” during which there is a complete collapse of central political authority. This is most likely to occur during periods of internal war.

If interregnums are indeed a good measure, the data show that “state failure” is primarily just an indicator of war. As the data show, the rate of “state failure” in the 20th century spiked in the two World Wars, and then increased again (but not as much) after decolonization, again almost always associated with wars.

Even this measure does not really capture the narrow definition. Many countries were often created as “states” by colonial powers rather than following any natural state-building process in which states gain more and more control of territory. Almost all ex-colonies fail to control national territory after independence, and many still do not do so today – many more than the usual number of “failed states.” (Africa being the most striking example as exposited in the great book by Herbst, States and Power in Africa. 4)

Hence, if we use the measure described above, than state failure is just synonymous with war, and if we don’t (as we probably shouldn’t), then “state failure” is something more common and harder to measure than the current policy discussion recognizes.

5) “State failure” appeared for political reasons.

The real genesis of the “state failure” concept was a CIA State Failure Task Force in the early 1990s. Their 1995 first report said state failure is “a new term for a type of serious political crisis exemplified by recent events in Somalia, Bosnia, Liberia, and Afghanistan.” All four involved civil war, confirming the above point that “state failure” often just measures “war.” And we have just seen from the data (and common sense about decolonization) that either the claim of “newness” is false, or we are still not sure what “state failure” means.

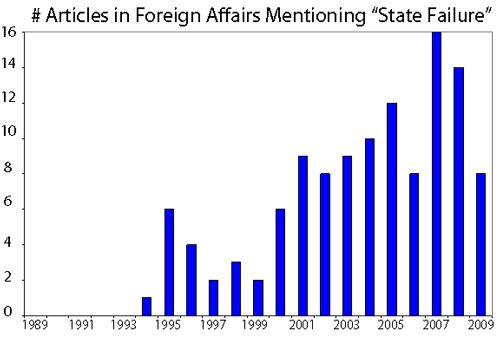

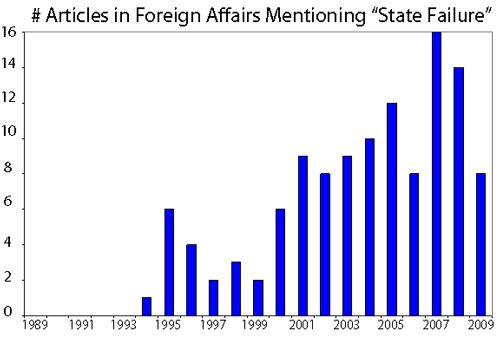

Nevertheless, “state failure” became a hot idea in policy circles. If we use the number of articles in Foreign Affairs mentioning “state failure” or variants, then it first appeared around the same time as the CIA task force, and then really took off after 9/11.

One can only speculate about the political motives for inventing an incoherent concept like “state failure.” It gave Western states (most notably the US superpower) much more flexibility to intervene where they wanted to (for other reasons): you don’t have to respect state sovereignty if there is no state. After the end of the Cold War, there was less hesitation to intervene because of the disappearance of the threat of Soviet retaliation. “State failure” was even more useful as justification for the US to operate with a free hand internationally in the “War on Terror” after 9/11.

One can only speculate about the political motives for inventing an incoherent concept like “state failure.” It gave Western states (most notably the US superpower) much more flexibility to intervene where they wanted to (for other reasons): you don’t have to respect state sovereignty if there is no state. After the end of the Cold War, there was less hesitation to intervene because of the disappearance of the threat of Soviet retaliation. “State failure” was even more useful as justification for the US to operate with a free hand internationally in the “War on Terror” after 9/11.

These political motives are perfectly understandable, but they don’t justify shoddy analysis using such an undefinable concept.

It’s time to declare “failed state” a “failed concept.”

[1] Kristie M. Engemann and Howard J. Wall, A Journal Ranking for the Ambitious Economist, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Review, May/June 2009, 91(3), pp. 127-39. We included all 69 journals that they studied, which they said were their meant to capture all likely members of the top 50.

[2] Sujai J. Shivakumar, Towards a democratic civilization for the 21st century, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, Vol. 57 (2005) 199–204.

[3] a through d: Robert I. Rotberg, Failed States in a World of Terror, Foreign Affairs. New York: Jul/Aug 2002. Vol. 81, Iss. 4; pg. 127.

[4] e through h: World Bank

[5] USAID Fragile State Strategy, 2005

[6] j through k: Fund for Peace

[7] l through m: Overseas Development Institute

[8] Monty G. Marshall and Keith Jaggers, Polity IV Project: Dataset Users' Manual, George Mason University and Center for Systemic Peace, 2009.

[9] Jeffrey Herbst, States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control, Princeton University Press, 2000.

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality

One can only speculate about the political motives for inventing an incoherent concept like “state failure.” It gave Western states (most notably the US superpower) much more flexibility to intervene where they wanted to (for other reasons): you don’t have to respect state sovereignty if there is no state. After the end of the Cold War, there was less hesitation to intervene because of the disappearance of the threat of Soviet retaliation. “State failure” was even more useful as justification for the US to operate with a free hand internationally in the “War on Terror” after 9/11.

One can only speculate about the political motives for inventing an incoherent concept like “state failure.” It gave Western states (most notably the US superpower) much more flexibility to intervene where they wanted to (for other reasons): you don’t have to respect state sovereignty if there is no state. After the end of the Cold War, there was less hesitation to intervene because of the disappearance of the threat of Soviet retaliation. “State failure” was even more useful as justification for the US to operate with a free hand internationally in the “War on Terror” after 9/11. News sources say that President Obama will choose “escalate” with additional troops for Afghanistan in his speech at West Point tonight. I and many like-minded individuals find this disastrous.

“Like-minded” means that critics of top-down state plans for economic development are also not fans of top-down state plans for military development. If the Left likes the first, and the Right likes the second, that just shows you how incoherent Left and Right are.

News sources say that President Obama will choose “escalate” with additional troops for Afghanistan in his speech at West Point tonight. I and many like-minded individuals find this disastrous.

“Like-minded” means that critics of top-down state plans for economic development are also not fans of top-down state plans for military development. If the Left likes the first, and the Right likes the second, that just shows you how incoherent Left and Right are.