The Androids are coming, is aid ready?

This post is the second in a series by Dennis Whittle. Dennis is the CEO of GlobalGiving, an international marketplace for philanthropy.

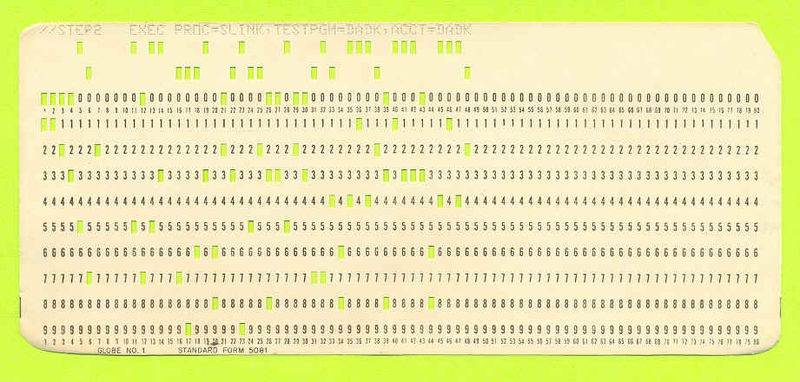

In my last post, I argued that the "operating system" used by the current international aid agencies is stuck using IBM punch cards while the rest of the world has moved on to cell phones, laptops, and iPhones.

In my last post, I argued that the "operating system" used by the current international aid agencies is stuck using IBM punch cards while the rest of the world has moved on to cell phones, laptops, and iPhones.

In the old system, you had to type programs into a stack of hundreds of punch cards, walk them down to the computer center, hand them to an operator, and wait in line for them to be processed. The lower you were in seniority, the longer you had to wait.

Contrast that with today, when hundreds of millions of people have their own computers, and several billion people have access to cell phones. iPhone and Android platforms now provide a way for hundreds of thousands of individuals to create and distribute new software. That software may or may not succeed in the marketplace, but it can be downloaded and used, and the most popular new apps get flagged to other users.

What would an analogous distributed operating system look like for the aid business? The design of any such operating system has to address five questions:

- Who decides which problems aid should address?

- Who comes up with the solutions?

- Who gives the funding?

- Who competes to implement the solutions?

- Who gives feedback on how well the solutions work?

The existing system is closed. It assumes these questions will be answered by experts within one of the "mainframe" organizations like the World Bank, the UNDP, USAID, or one of the big NGOs.

Unlike 60 years ago, the expertise, resources and technology now exist to make a new decentralized and distributed aid system possible. Many more people—and not just experts—have relevant developing country experience (for example, the Peace Corps alone has over 250,000 alumni). Regular Americans give over $25 billion each year to charitable causes abroad—about the same amount as the US official aid budget. And PCs, internet, cell phones and related technologies now make it possible to connect all of these people and resources directly to the people who need help.

Marketplaces that directly connect funders to projects include GlobalGiving, DonorsChoose, MissionFish, GiveIndia, HelpArgentina, Conexion Columbia, Betterplace (Germany), GreaterGood South Africa, Net4Kids (Netherlands). Markets need quality information, and groups such as Guidestar, New Philanthropy Capital, GiveWell, Great NonProfits, Philanthropedia, Keystone Accountability, Charity Navigator, and the BBB Wise Giving Alliance have begun to operate mechanisms that collect and make available data from a wide variety of sources. Technology startups such as Frontline SMS and Ushahidi are making it possible for beneficiaries to have direct input into what they need ex-ante (schools? health clinics? microcredit?) and how well projects are being implemented once underway. Other initiatives (for example, Jumo) are in the planning stages.

Not all of these new initiatives will succeed. But within a few years, it will be possible for any person or group in the world to help answer any of the five questions above that form the core of the aid operating system. If the existing agencies that run closed systems don't adapt to this new set of conditions, they will become as irrelevant as old IBM mainframes.

--

Related post: Is aid stuck using IBM punch cards?

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality