Hopeless cause of the week: save Madagascar!

Aid Watch has a stubborn attachment to excellent but possibly hopeless causes… Madagascar, a country we first blogged about in June and then again in August, may be down to its last few days as regards AGOA, the US preference program that underpins about 50 percent of the country's $500 million textile industry. Because of the change of government that took place in Madagascar in March, the US has been steadily threatening to suspend its AGOA eligibility unless the country returns pronto to constitutional government. A committee consisting of representatives from State, Commerce, Labor, Treasury, USAID, the NSC and the USTR has been deliberating for several days on whether Madagascar's transgressions merit suspension from AGOA.

With little likelihood that egregious democracy and human rights violators like Gabon and Angola will be suspended from AGOA, it's hard not to be cynical about why Madagascar has come under such scrutiny for a regime change in which a highly experienced kleptocrat was replaced by a less experienced one. Or why, suddenly, there is such concern about a return to constitutional government when it's not at all clear that Madagascar's leaders over the last 40 years have ever placed the interests of their people above their own. We can be fairly sure that if Madagascar were pumping oil instead of just looking for it the country's AGOA status would not even be under consideration. Still, we’re going to try not to be cynical.

We don’t know WHAT the AGOA eligibility committee on Madagascar is talking about. (The committee doesn't actually make the final decision on AGOA. They make a recommendation to the president who typically announces who's in and who's out around Christmas time.) But we imagine the discussion breaks down in two ways. On one side, there are the idealists who believe that the AGOA goals of promoting democracy and good governance will never be achieved unless the US gets serious about sanctioning individuals who overthrow democratically elected governments. After seeing Madagascar's political leaders backslide, prevaricate and just plain lie about their intentions in on-going negotiations brokered by the AU, SADC and the UN, the idealists are skeptical about whether these leaders - none of whom is a poster child for good governance - are serious about resolving their long standing differences. The idealists are probably right. These political adversaries, who have overthrown one another like kids playing leapfrog, despise each other. We can expect that, AGOA or no AGOA, political friction, back-stabbing and jockeying for position will continue in Madagascar for years to come - just like in most countries.

On the other side of the committee table, there are the realists who recognize that cutting off AGOA is unlikely to have any effect on those behind the overthrow of the previous government but will vaporize millions upon millions of dollars of foreign investment in Madagascar, some of it by US companies, and dump tens of thousands of young female workers trying to feed their kids into the streets.

So what to do? Cancel AGOA in support of a principle that will do nothing to advance good governance in Africa, or continue it and support workers and investors who had nothing to do with the whole business? Forgive us for our presumption that this is a fairly obvious call.

This is an interesting test of whether independent observers who actually care about Madagascar have any effect on US government decisions in our democracy, or whether the departments concerned simply act with impunity to pursue their own interests and agendas. The rest is up to you, most esteemed AGOA committee. -- Update: Take action on this cause! Send an email to Florizelle Liser (Florie_Liser@ustr.eop.gov), Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Africa, telling her not to cancel AGOA in Madagascar.

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality

At home, we don’t value people around us only by their numerical income – we also recognize courtesy, classiness, intelligence, loyalty, familial devotion, community dedication, spirituality, peacefulness, creativity, beauty, style, kindness, athleticism, artistry, and many other dimensions.

At home, we don’t value people around us only by their numerical income – we also recognize courtesy, classiness, intelligence, loyalty, familial devotion, community dedication, spirituality, peacefulness, creativity, beauty, style, kindness, athleticism, artistry, and many other dimensions.

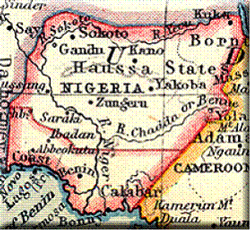

In colonial Nigeria in the last years of the 19th century, a strange quirk of history led the British rulers to draw an arbitrary boundary line along the 7˚10' N line of latitude, separating the population into two separate administrative districts.

In colonial Nigeria in the last years of the 19th century, a strange quirk of history led the British rulers to draw an arbitrary boundary line along the 7˚10' N line of latitude, separating the population into two separate administrative districts. In a recent experiment, a team of scientists trained a vervet monkey to open a container of apples, a task no other monkey in her group could do. She was well-compensated for this service by the other monkeys, who began to spend a lot of time grooming her (apparently, grooming is the monkey unit of exchange). Then, the scientists trained another monkey in the group to get the apples, and the “price” for the service (ie the amount of grooming the apple-providing monkeys received) went down.

In a recent experiment, a team of scientists trained a vervet monkey to open a container of apples, a task no other monkey in her group could do. She was well-compensated for this service by the other monkeys, who began to spend a lot of time grooming her (apparently, grooming is the monkey unit of exchange). Then, the scientists trained another monkey in the group to get the apples, and the “price” for the service (ie the amount of grooming the apple-providing monkeys received) went down.  I recently helped one of my single male graduate students in his search for a spouse.

First, I suggested he conduct a randomized controlled trial of potential mates to identify the one with the best benefit/cost ratio. Unfortunately, all the women randomly selected for the study refused assignment to either the treatment or control groups, using language that does not usually enter academic discourse.

I recently helped one of my single male graduate students in his search for a spouse.

First, I suggested he conduct a randomized controlled trial of potential mates to identify the one with the best benefit/cost ratio. Unfortunately, all the women randomly selected for the study refused assignment to either the treatment or control groups, using language that does not usually enter academic discourse.