Does Japan need your donation?

Many aid bloggers and journalists are doing a good job communicating a nuanced message about how to respond to the devastating earthquake and tsunami in Japan. From Stephanie Strom, writing in the New York Times:

The Japanese Red Cross…has said repeatedly since the day after the earthquake that it does not want or need outside assistance. But that has not stopped the American Red Cross from raising $34 million through Tuesday afternoon in the name of Japan’s disaster victims…

The Japanese government so far has accepted help from only 15 of the 102 countries that have volunteered aid, and from small teams with special expertise from a handful of nonprofit groups…

…[M]any of the groups raising money in Japan’s name are still uncertain to whom or to where the money will go…

Holden Karnofsky, a founder of GiveWell, a Web site that researches charities, said he was struck by how quickly many nonprofit groups had moved to create ads using keywords like “Japan,” “earthquake,” “disaster,” and “help” to improve the chances of their ads showing up on Google when the words were used in search queries.

“Charities are aggressively soliciting donations around this disaster, and I don’t believe these donations necessarily are going to be used for relief or recovery in Japan because they aren’t needed for that,” Mr. Karnofsky said. “The Japanese government has made it clear it has the resources it needs for this disaster.”

Robert Ottenhoff, president and chief executive of GuideStar, a Web site that provides charity tax forms and other resources for donors, said donors themselves were to blame for the fund-raising frenzy.

People who really want to support charitable organizations and good works, Mr. Ottenhoff said, should base it on a desire to support something they already understand and believe in.

The Japanese are world-renowned experts in disaster preparedness, relief and recovery, and Japan is the third largest economy in the world. There should be no mistake that the Japanese government and Japanese organizations are well-equipped to take the lead.

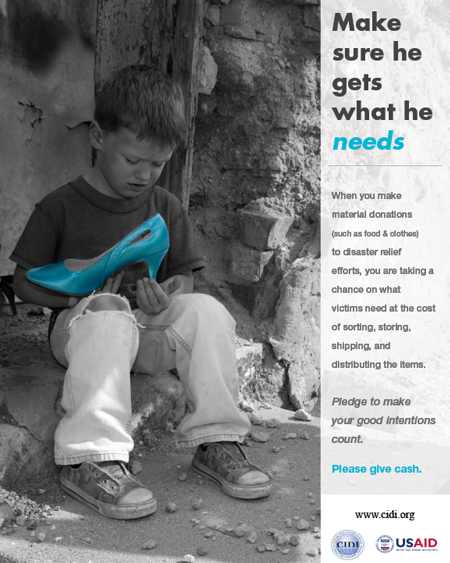

Our best advice for people who feel moved to give by the tragedy in Japan: Give generously, in cash, to an organization that you trust, and don’t restrict your donation. This way, your charity can use the funds for Japan if it turns out they are needed. If not, then it is free to use your donation for another purpose, like the dozens of under-reported, large-scale disasters that CNN isn’t featuring today.

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality