Take seriously the power of networks (or just look at some COOL maps)

A few days ago, I met a guy because he was my wife’s girlfriend’s boyfriend. He turned out to be a high ranking official who had some fascinating inside stories about aid and corruption in an African country (which I won’t name to protect his privacy). A local aid worker friend recommended an orthopedist to treat my wife’s badly injured ankle while we were in Addis Ababa. The orthopedist was able to give my wife relief (at full American prices, which went to his NGO) and then he asked if I knew that crazy aid criticizing NYU professor.

One of the best hiring decisions I ever made was to employ my friend’s wife’s neighbor’s daughter.

More and more people are discovering the power of social networks (consult the avalanche of popular books on connectedness and shrinking degrees of separation). Being well-connected to other people, who are in turn well-connected, is a powerful way to get information, to reduce search costs for employment or trade transactions, and to create strong incentives to behave well and protect your own reputation. Formal research in economics celebrates the economic payoff to social connectedness (aka social capital). Phenomena like the Hasidic diamond merchants of 47th street in Manhattan show the power of business networks based on ethnicity and family. Ethnic networks are common in Africa, like the Hausa traders in West Africa, or Luo fish merchants in Kenya.

The scorn usually shown for Nepotism and the Old Boy Network is so 20th century! The 21st century view is to respect the value of social connections wherever they come from!

OK, I’m exaggerating. You need to balance the value of social connections against accountability mechanisms, merit-valuing incentives, and ethical rules, so I don’t just hire my good-for-nothing cousin with other people’s money. Also you need to worry about people who are frozen out of networks through no fault of their own. But that is OFF MESSAGE, so I am going to ignore all that today.

Venture capitalists rely heavily on social networks to assess reputation and to make new deals. And so do social entrepreneurs. Someone tipped me off to xigi.net, which is a fantastic web site for facilitating networks among social entrepreneurs:

xigi.net (pronounced 'ziggy' as in zeitgeist) is a space for making connections and gathering intelligence within the capital market that invests in good. It’s a social network, tool provider, and online platform for tracking the nature and amount of investment activity in this emerging market.

OK, I confess, what really got me to look at this site was the hyper-cool network maps that show connections between the social entrepreneurs. Check out the map for the deservedly well-connected Ashoka folks of Bill Drayton (this is a screen shot, but you have to visit the map on the xigi site to explore its cool functionality).

The point is that part of the effectiveness of Ashoka is because they are so well connected, and they make all their partners in turn more effective in turn by being connected to the well-connected Ashoka.

We could keep dreaming: social networks could be a powerful vehicle for spreading information and evaluations about existing aid projects and actors. The Internet makes this much more feasible that it used to be. GlobalGiving.org is one initiative that tries to implement this idea. Oh, and I happen to know about and trust GlobalGiving because I have known the two founders ever since we worked together on Russia in the early 90s.

I had never heard of xigi.net until a couple days ago. I heard about it from my wife’s girlfriend, the one who had the aid and corruption story-telling boyfriend.

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality

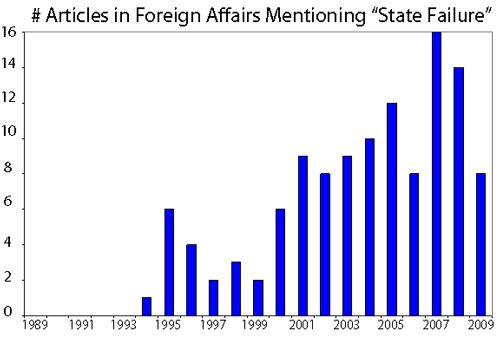

One can only speculate about the political motives for inventing an incoherent concept like “state failure.” It gave Western states (most notably the US superpower) much more flexibility to intervene where they wanted to (for other reasons): you don’t have to respect state sovereignty if there is no state. After the end of the Cold War, there was less hesitation to intervene because of the disappearance of the threat of Soviet retaliation. “State failure” was even more useful as justification for the US to operate with a free hand internationally in the “War on Terror” after 9/11.

One can only speculate about the political motives for inventing an incoherent concept like “state failure.” It gave Western states (most notably the US superpower) much more flexibility to intervene where they wanted to (for other reasons): you don’t have to respect state sovereignty if there is no state. After the end of the Cold War, there was less hesitation to intervene because of the disappearance of the threat of Soviet retaliation. “State failure” was even more useful as justification for the US to operate with a free hand internationally in the “War on Terror” after 9/11.