It is an acknowledged national characteristic that Americans believe in self-reinvention. One of our founding myths—inspired by the once unexplored and sparsely populated expanse of the North American continent—is the idea that you can head out of town, leave the encumbrances of the past behind, and start over in a new, unspoiled place.

What would happen if we brought this sensibility to development plans for poorer, more crowded nations? What if we already do?

The ingredients for Paul Romer’s solution to global poverty include an unoccupied tract of land, a charter to lay out a new set of just and commerce-promoting rules, and two or more sovereign governments. Just as Hong Kong was created as an island of prosperity by the British in China (only voluntarily this time), poor countries would lease a piece of their land to a richer, benevolent government or group of governments that would agree to administer the new city according to the rules of the agreed-upon charter.

From a new article in Atlantic Monthly by Sebastian Mallaby, we learn that Madagascar might have become the first testing ground for Romer’s charter cities idea—if not for a coup that ousted the Malagasy President in March 2009.

Madagascar’s government was anxious to attract foreign investment, and it understood that a credibility deficit held it back…Faced with this obstacle, the Malagasy authorities were open to unconventional arrangements. To boost investment in agriculture, they were ready to lease a Connecticut-size tract of land to Daewoo, a South Korean corporation, for 99 years…Romer’s proposal fit in with these adventurous ideas.…

Romer made his pitch for a charter city, and Ravalomanana responded that he wasn’t sure one was enough; if Romer could identify two rich countries willing to play the role of government trustee, it might be better to launch two parallel experiments. The president and the professor agreed that the new hubs should be open to migrants from nearby countries as well as to locals. They rose to examine a map of Madagascar on the study wall. Ravalomanana suggested building the first city on the island’s southwestern coast, which was largely uninhabited because of its dry heat. To Romer, the site sounded very much like the coastal locations that appeal most to the world’s affluent as vacation spots.

Ravalomanana’s government was toppled before any of these plans could go forward, in part as a result of violent protests over the perceived threat to national sovereignty represented by the Daewoo deal. As Mallaby points out, this failures suggests at least one flaw of the charter cities idea—that land ownership and sovereignty are explosive issues that may not be easily or peacefully negotiated away by leaders on behalf of their people. But Romer remains optimistic, and is talking to other African leaders, possibly ones with more staying power.

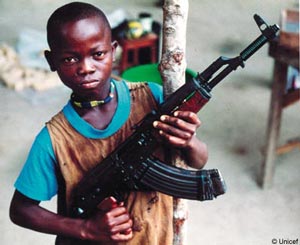

The charter cities idea appeals because it is bold. It promises a fresh start for people mired in the muck of old conflicts, inequality, and bad government. When Mallaby concludes “When African teenagers do their homework under streetlights, isn’t Romer right to think the unthinkable?,” he is arguing that while there may be legitimate concerns about the ethics or feasibility of the charter cities, those concerns are made irrelevant by the overwhelming gravity and scale of global poverty and inequality.

In other words, big, desperate problems call out for big, radical solutions. Solutions that sweep away the detritus of past failure, promise to replace it wholesale with something new and better, and perhaps even alter the boundaries of the world as we know it.

The discussion about rebuilding Haiti has been full of ideas about the earthquake as an opportunity to ”start over,” “reboot,” “wipe the slate clean” and finally “get things right” (some stellar examples here). Two recent proposals brought the call for slate-cleaning back to Africa: We already blogged Professor Pierre Englebert’s suggestion in the NYT for the international community to “move swiftly to derecognize the worst-performing African states” like Chad, the DRC, Equatorial Guinea and Sudan, and in Foreign Policy, G. Pascal Zachary submitted that “no initiative would do more for happiness, stability, and economic growth in Africa today than an energetic and enlightened redrawing” of Africa’s colonial borders.

Call it the “let’s just scrap this mess and start over” approach to development.

Unfortunately, in earthquake-devastated Haiti as in troubled central Africa, the promise of starting from scratch is an illusion. It has always been true that no matter where you go, you take yourself with you—culture, history, habits, attachments and animosities come along like a skin you can’t shed. But these days there are fewer and fewer territories on our taxed and shrinking planet beyond the reach of someone’s determined claim.

These ideas share an overly-optimistic belief in a neutral, benevolent international community and its power to peacefully oversee imposed changes. All are tone-deaf to the very real degree of nationalism that does exist in basically all countries by now, regardless of whether they were misbegotten colonial creations or not. They also violate sovereignty as conventionally defined, which may be good or bad but is sure to provoke a nationalist reaction.

Early development economists working at the hopeful dawn of colonial independence believed that they really were starting from scratch. The last fifty years have shown us that they weren’t, and this has been—and remains—one of development’s biggest blind spots.

You can see why anti-immigration sentiment is a big deal in the European countries shown and in the US. (This is a descriptive statement, I myself hate xenophobia.)

You can see why anti-immigration sentiment is a big deal in the European countries shown and in the US. (This is a descriptive statement, I myself hate xenophobia.) From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality