How Not to Teach Children about Poverty

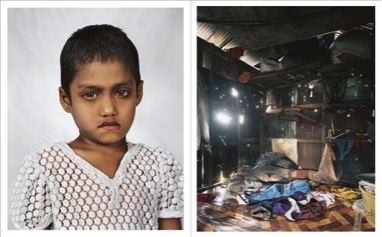

Meet Shameela, 5, a stateless child from a Thai refugee camp. Shameela’s battered shack has holes in the roof and walls. She has to share an outdoor bathroom with 100 other people. Shameela is crying while a photographer takes her portrait.

Meet Shameela, 5, a stateless child from a Thai refugee camp. Shameela’s battered shack has holes in the roof and walls. She has to share an outdoor bathroom with 100 other people. Shameela is crying while a photographer takes her portrait.

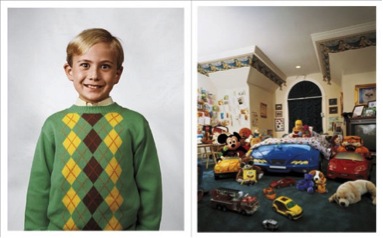

Meet Harrison, 8, who lives with his parents in a New Jersey mansion with a marble staircase. He has his own bedroom with a flat screen television. Harrison’s clothes are neat and his smile is calm.

Shameela and Harrison, along with 54 other kids and teenagers around the world, are part of a beautiful glow-in-the-dark photobook called Where Children Sleep. To make it, photographer James Mollison traveled around the world to take snapshots of children and places they call their bedrooms.

Mollison has a cosmopolitan background — he was born in Kenya, grew up in the UK, and is now based in Venice. Book reviews mention this fact as if to suggest how broad-minded and fit for the job it made him. “To begin with, I called the project ‘Bedrooms,’” says Mollison in the book’s foreword, “but I soon realized that my own experience of having a ‘bedroom’ simply doesn’t apply to so many kids.”

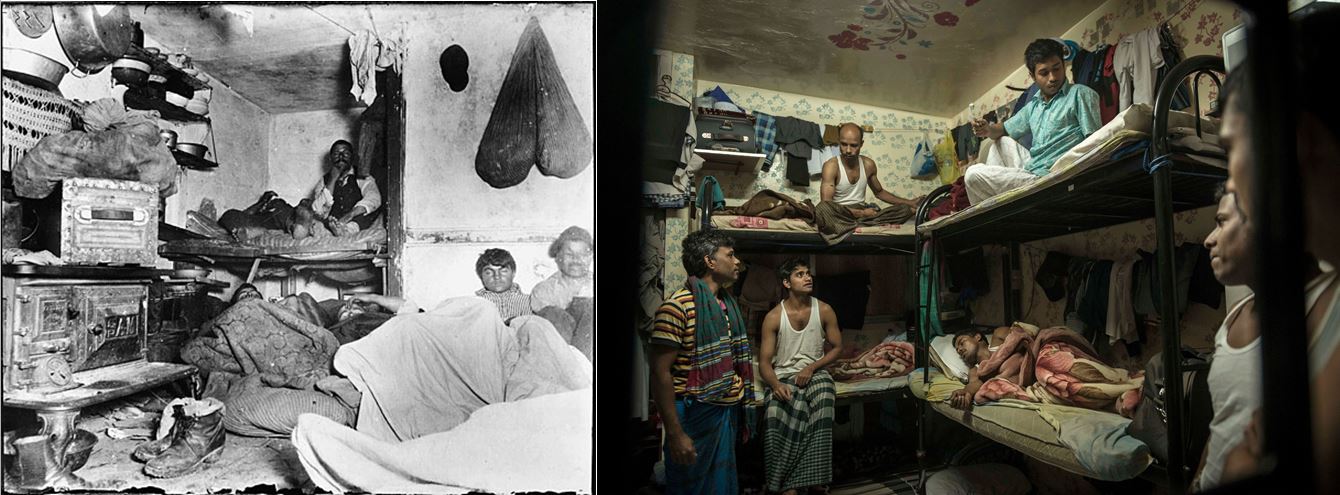

The photographer embarked on the project trying to avoid clichés: “From the start, I didn’t want it just to be about ‘needy children’ in the developing world, but rather something more inclusive, about children from all types of situations.” Yet half of his images are of deprived children from developing countries, and another quarter are of well-to-do Western kids who in comparison look unallowably privileged.

The poverty and inequality landscape is not what it was, and certainly not what it is often believed to be. Most of the world’s poor now live in middle-income countries. The United States is now almost as unequal as Brazil. Yet in Mollison’s collection four out of five Brazilian kids reside either in favelas or on the street, while nine out of eleven American kids enjoy expensive hobbies, New York City penthouses, or marble-staired castles. In Nepal, one can’t deny that income statistics are dire: 25% of the population lives below the national poverty line (about $15 a month). Yet Mollison’s sample selection distorts this image further — five out of his eight Nepalese models are abjectly poor.

Each photo on its own tells a deep, complicated, and often hopeful story. Shameela is the first girl in her family to go to school. Preena, a young Nepalese housemaid, sends remittances to support her family in the village. Sherap goes to a Tibetan monastery school and admires his teacher. But when all the photographs are put together into a 120-page book, the story changes.

Mollison says he wants his book to help kids learn about poverty and inequality, “and perhaps start to figure out how, in their own lives, they may respond.” Yet unintentionally, the misguided and often harmful stereotype that some of us can and should fix the lives of others is passed on from our generation to the next.

This photobook can enrich a child’s worldview. It will familiarize children with ethnic conflict, public health issues, cultural prejudices, and more. But to educate kids about inequality and poverty – ideally before they spend their gap year and thousands of airfare dollars on a questionable voluntourism stint – you might need to find other didactic material.