by Francisco Rodríguez, Head of Research at the Human Development Report Office

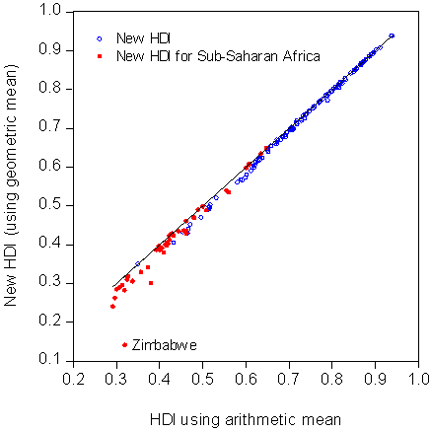

In a post published last Thursday, Bill Easterly and Laura Freschi criticize the new formula for the Human Development Index (HDI) introduced in this year’s Human Development Report. Borrowing on a recent paper by the World Bank’s Martin Ravallion, Easterly and Freschi argue that our decision to shift from an additive to a multiplicative mean makes Africa look much worse than it should.

The relevant question, of course, is not whether the index makes any particular region or country look better or worse but whether the methodological changes introduced in the new version of the HDI make sense. If we reject the methodology, we should do it based on the soundness of its principles, not on whether or not we like its conclusions.

Why the HDI has a new functional form – and what it means

One of the key changes to the HDI functional form introduced in this year’s report was to shift from an arithmetic to a geometric mean, thus introducing imperfect substitutability into the index. Imperfect substitutability means that the less you have of something, the more you will benefit from improvements in that dimension. By contrast, perfect substitutability (which had characterized the index’s old formula) means that how much you care about one dimension has nothing to do with its initial value. The old perfect substitutability assumption had been extensively criticized, with good reason.{{1}}

Easterly and Freschi misinterpret the rates of substitution in the HDI as saying something about the “value” of a life. But the HDI is not a utility function, nor is it a social welfare function. It is an index of capabilities.{{2}} What the huge differences in trade-offs between health and income in the index tell us is actually something quite simple: that income contributes very little to furthering capabilities in rich countries. Societies may and do value other things than their capabilities, so it is incorrect to read these numbers as “values” of anything.

For more on why it is incorrect to read “values” into the HDI, read the longer version of this article.

Does the new HDI make Sub-Saharan Africa look worse?

What is the net effect of the new functional form on the relative position of Africa vis-à-vis the rest of the world? In the 2010 Human Development Report, Africa’s average HDI stands at .389, or 62.3 percent of the world HDI. If we had applied the old functional form, then Africa’s HDI would have been 64.1 percent of the world average. So does the new HDI make Africa look worse? Yes, exactly 1.8 percentage points worse. While one can of course try to make a big deal about that, as Easterly and Freschi do picking up on the former’s earlier complaints about the MDGs, it seems that nothing in the general picture of Africa’s relative progress vis-à-vis the rest of the world really changes from the new functional form.

Easterly and Freschi also object to the HDR’s measure of progress, which they claim is biased against Africa. First of all, it is not clear that it would be a good thing if a measure of progress ranked Africa highly for the past forty years, a period that includes the disastrous 1980s. But if they were right and our measure was incapable of capturing African progress, then we shouldn’t see Africa do well in any period. However this is not the case. Indeed using the same measure of progress, Africa does remarkably well since 2000. As shown in Table 1 below, Africa has six of the top 10 performers in the world, including all the top five (Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Mali, Mozambique and Burundi). Odd results indeed for an index which by design is claimed to be biased against Africa.

For more on Africa’s human development progress, read the longer version of this article.

References

Desai, Meghnad (1991), ‘Human Development: concepts and measurement’, European Economic Review 35, p. 350–357.

Lind, Niels (2004), 'Values Reflected in the Human Development Index', Social Indicators Research 66, p. 283-293.

Sagar, Ambuj and Adil Najam (1998), ‘The Human Development Index: A Critical Review’, Ecological Economics 25, no. 3, June, p. 249-264.

Sen, Amartya (1980), “Equality of what?”, in S.M. McMurrin (Ed.), Tanner Lecture on Human Values, Vol. I, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

UNDP(2010) The Real Wealth of Nations: Pathways to Human Development. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

[[1]]See, for example, Desai (1991), Sager and Najam (1998), Lind (2004).[[1]]

[[2]]For the notion of capabilities and its relationship to the human development approach, see Sen (1980).[[2]]

--

Related posts:

The First Law of Development Stats: Whatever our Bizarre Methodology, We make Africa look Worse

What the New HDI tells us about Africa

Human Development Index Debate Round 2: UNDP, you’re still wrong

From Aid to Equality

From Aid to Equality

From the brilliant

From the brilliant